Being the father of a 3 year old, we watch a fair amount of animation in our house. You hear of social critics bewailing the pernicious effect of tv and cartoons on children, yet it’s really the parents we should all be worrying about. As soon as I heard the phrase ‘data mining’, the first thing which entered my mind was, “we dig, dig, dig, dig, dig, dig, dig, in a mine the whole day through”. Unlike the dwarfs however, it’s not diamonds we’re after, but gems of information and meaning in big data.

In the pre-digital age, text analysis was a long manual process and there were human limits as to how many texts could be read and compared. Nowadays however, there exists a vast digital corpora and the technology to search, read and analyse it. This automated process is usually referred to as Data Mining.Data Mining presents tremendous opportunities to the researcher, and in our lecture this week, Ulrich Tiedau, Associate Director of the Centre for Digital Humanities at UCL, illustrated this to our class by showing its application to the Digital Humanities. He explained how he and his colleagues were examining Asymetrical Encounters between Reference Cultures and those of the Low Countries (Belgium, Netherlands and Luxembourg). It’s a study of six countries over two centuries, and relies on analysing long runs of data contained within digitised newspaper collections. A new text mining tool called Texcavator has been developed in order to search through the Dutch Digital Library, Europeana (a collection of digitised European newspapers) and other collections.

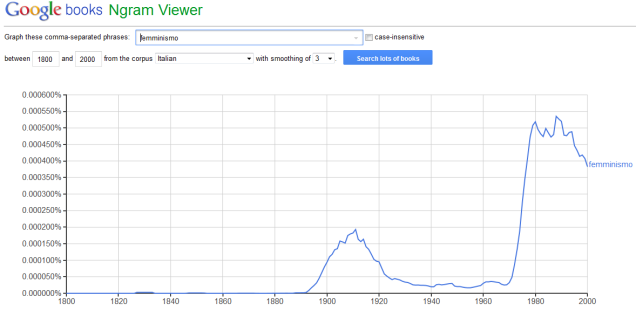

Ulrich went on to explain two other examples. Firstly, the way in which Google’s Ngram Viewer (by visualising the frequency of a word in a corpora of books over time), can stimulate research questions; e.g from the graph below, what can account for the rises and falls of ‘feminism’ in Italy during the Twentieth Century?

Finally, he explained how Topic Modelling can be used, in which an algorithm conducts a statistical analysis of the corpora in order to group together sets of words which tend to appear together. This is quite an interesting take on text analysis / data mining, because rather than feeding in keywords, instead, you can just see what patterns are thrown up.

In the lab I began to put these ideas into practice by: exporting data from the Old Bailey online API to voyant; and, by examining the Aysmetrical Encounters research project of the Utrecht University Digital Humanities Lab.

With Altmetrics I’d been looking at the issue of the Civil Rights Movement in the USA, so it made me curious as to whether there had been any convictions at the Old Bailey for offences involving race riots. I firstly, searched the Old Bailey Online database with the key word ‘race’ and filtering for the offence of ‘Breaking Peace > riot’. There were only two results and in both cases the word race was from a different context to my query. I repeated the search for keywords ‘African’, ‘Negro’, ‘Jew’, ‘Alien’, ‘Foreign’ and ‘German’ but received no results. This doesn’t prove that there were no race riots in the period 1674-1913, only that there were no convictions. Obviously, these searches weren’t great for data mining, since I had no data!

I then decided to examine those crimes which had resulted in the death penalty, since I knew there would be plenty of data, and I was correct. I searched over the whole period, 1674-1913 and carried out separate filtered searches by the crimes they were convicted of. The results were as follows: Breaking Peace (198); Damage to Property (35); Deception (442); Killing (442); Miscellaneous (295 – of which 259 were for Returning from Transportation); Royal Offences (568); Sexual Offences (142); Theft (6357); Violent Theft (2340). As I suspected, the range of reasons for which people were sentenced to death in the past was pretty vast and was overwhelmingly for non-violent crimes.

I then went to the site’s API Demonstrator, which allows the user to export results to voyant for text analysis, or to the bibliographic management system Zotero. The API was structured slightly differently to the original search, with the two key differences being: that using the API you are able to search by the gender of the offenders and victims; whereas in the original search you are unable to do so, but you can search for names of offenders and victims. I’m not really sure why both features aren’t available in both formats, since they are potentially very useful.

Using the API I decided to narrow my investigation by focusing on Royal Offences, and sent two sets of search results to voyant. Royal Offences resulting in the death penalty between 1674-1694, and secondly, between 1822-1842 (the last year in which a person was executed for a Royal Offence). I wanted to examine two samples, in two periods, but over a similar period of time, in order to see the extent of similarity or difference between them. The results were exported to Voyant for further analysis.

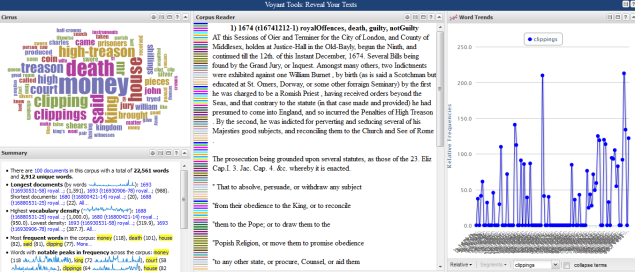

A good feature of the link between the API and Voyant is the fact that stop words are automatically applied, however, it makes sense to add custom words such as ‘prisoner’ ‘court’ ‘indictment’ etc which relate just to the trials rather than the cases themselves. The image below show the reults of the1674-1694 search exported to Voyant (the search yielded 103 hits, of which the first 100 were exported). The resulting word cloud shows that there were two main types of offence within this category, and they were high-treason, and the clipping of coinage. A search on the frequency of the word clipping shows a pattern of peaks and troughs. This information could be used for further research if it was overlaid with statistics on inflation or other economic data in order to build up a greater understanding of the economic circumstances at the time.

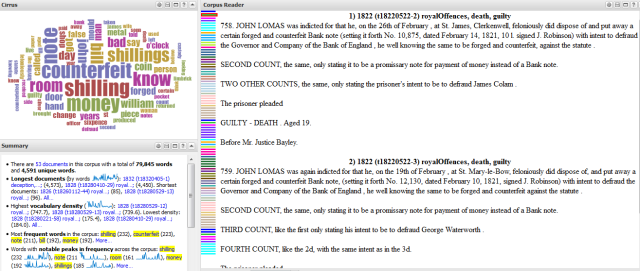

The image below show the results of the exported search on the period 1822-1842. Over this period the search yielded 52 results, (of which all 52 were exported to Voyant) half the number from the earlier period. The word cloud shows a significant difference from the one above, most noticeably, the fact that there were no incidences of ‘high treason’, and that crimes to do with money had changed in nature from ‘clipping’ to ‘counterfeiting’.

As I think I’ve shown, even a very cursory use of these tools can deliver very revealing results for a researcher, and with greater experience, skill and focus, a user will find them very useful indeed. I’d just like to give a big thank you to Professor Tim Hitchcock (@TimHitchcock), director of the Old Bailey Online project, and Dr Sharon Howard (@sharon_howard), project manager, who both helped me out when I had a few technical difficulties. For those of you who are interested, Sharon Howard has a blog, ‘Crime in the Community‘ which examines the Old Bailey Online, and the London Lives projects in greater depth.

Finally. I spent some time examining the website of the Asymetrical Encounters research project. It’s still very much an ongoing project and at present is very much describing its work in the future tense rather than as a set of results, as you can see from this screen grab below.

The project includes links to Conferences and the article ‘Big Data for Global History’ outlining the process of undertaking such an ambitious task. Clearly, it’s in the scope of the project where this diverges most radically from the Old Bailey Project. Being transnational in character, research into Asymetrical Encounters faces far more challenges, such as gaining full access to the digitized newspaper collections of all the countries in the study; nevertheless, I look forward to reading about their findings in the future.

Data mining opens up a world of possibilities for research, yet there are still obstacles in place, as outlined by Michelle Brook, Peter Murray-Rust and Charles Oppenheim in their 2014 article, ‘The Social, Political and Legal Aspects of Text and Data Mining (TDM)‘. Chiefly, these are to do with users and the law. Firstly, there is a lack of awareness among many academics of the opportunities TDM presents and many lack the technological skills and confidence to use the available resources. Secondly, although there have been recent changes to UK copyright law, there are still issues regarding the mining of data from other jurisdictions and many issues have still not yet been tested / established in the courts, and this can lead to some reluctance on the part of publishers and academics.

Interesting analysis, I especially liked how you used the Old Bailey API with Voyant to compare the two time periods and pick out differences – a good example of how tools like these can be used to accompany serious historical research.

LikeLike

Nice write up. I liked the way you customised the stop words in Voyant to remove the procedural grammar layer from the corpus so you could get deeper into the text.

LikeLike